Climate Reparations Debt: Who Pays for Dubai Floods & Canada Wildfires? (Insurance Crisis)

Climate Reparations Debt: Dubai Floods & Canada Wildfires

The global climate crisis is rewriting the rules of economics, debt, and disaster response. From the record-breaking floods in Dubai to the devastating wildfires across Canada, the financial toll is escalating, and a contentious question has resurfaced: who should pay for the damage? Governments, insurers, fossil fuel giants, and international funds are all part of the debate, but none seem able—or willing—to bear the rising costs alone.

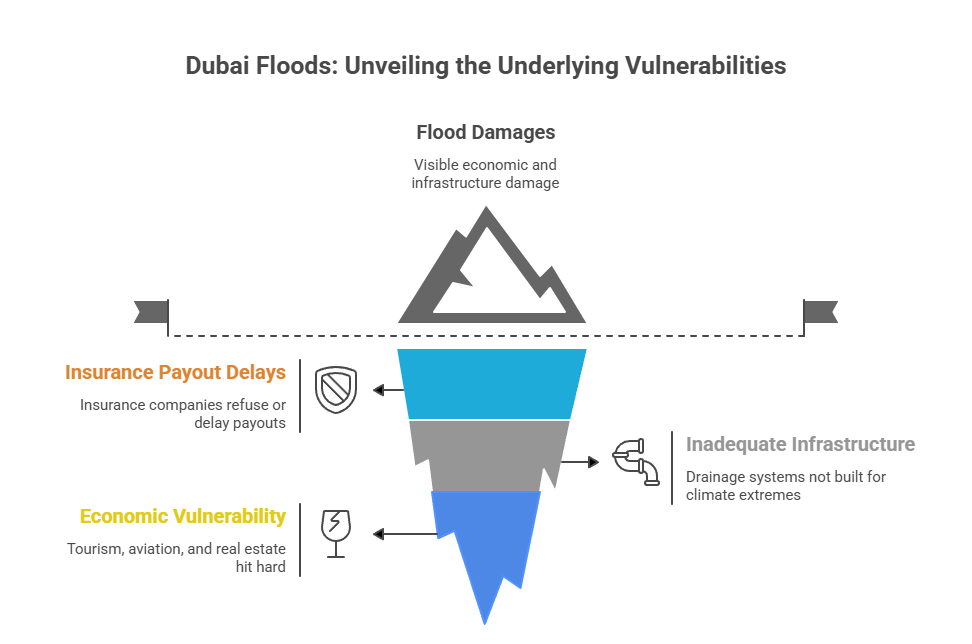

Dubai Floods: A Billion-Dollar Disaster

In early 2025, Dubai experienced its heaviest rainfall in more than 50 years. Flash floods swept through highways, luxury shopping malls, and densely populated neighborhoods. Cars floated like toy boats, metro stations closed, and airports halted operations as the city struggled to cope.

Officials estimate that damages could exceed $5 billion, with tourism, aviation, and real estate—the very backbone of Dubai’s economy—among the hardest hit sectors.

Yet for many homeowners and businesses, the financial pain is just beginning. Insurance companies across the Gulf are refusing or delaying payouts, citing force majeure clauses and climate-related exclusions in contracts. Families who lost homes are left to rebuild on their own, while small businesses without coverage face permanent closure.

The floods also exposed the city’s vulnerability: despite its reputation for futuristic infrastructure, Dubai’s drainage systems and urban planning were not built for climate extremes of this magnitude.

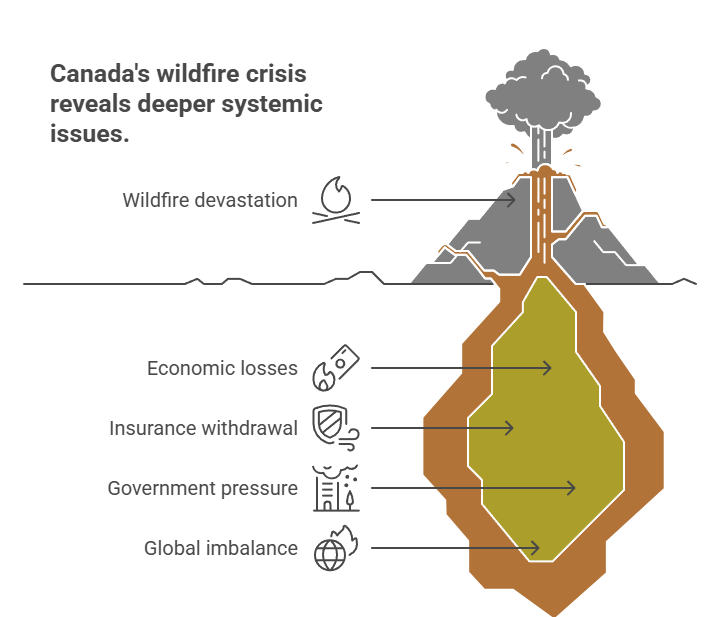

Canada Wildfires: A Nation on Fire

Thousands of kilometers away, Canada is fighting its worst wildfire season on record. Entire communities have been evacuated, forests spanning more than 20 million hectares have burned, and smoke has choked skies as far away as Europe.

Economic losses are staggering. Insured damages are estimated at $9–10 billion, making it the costliest wildfire disaster in Canadian history. But as with Dubai, insurance companies are pulling back. In provinces such as Alberta and British Columbia, several insurers have withdrawn from offering new wildfire coverage, leaving families unable to insure their homes at any price.

The Canadian government is under pressure to create a national disaster insurance program, similar to schemes in the UK and US, to protect citizens in high-risk zones. But that raises a larger issue: how long can governments keep bailing out victims of climate disasters without addressing the global imbalance of responsibility?

The Global Climate Reparations Debate

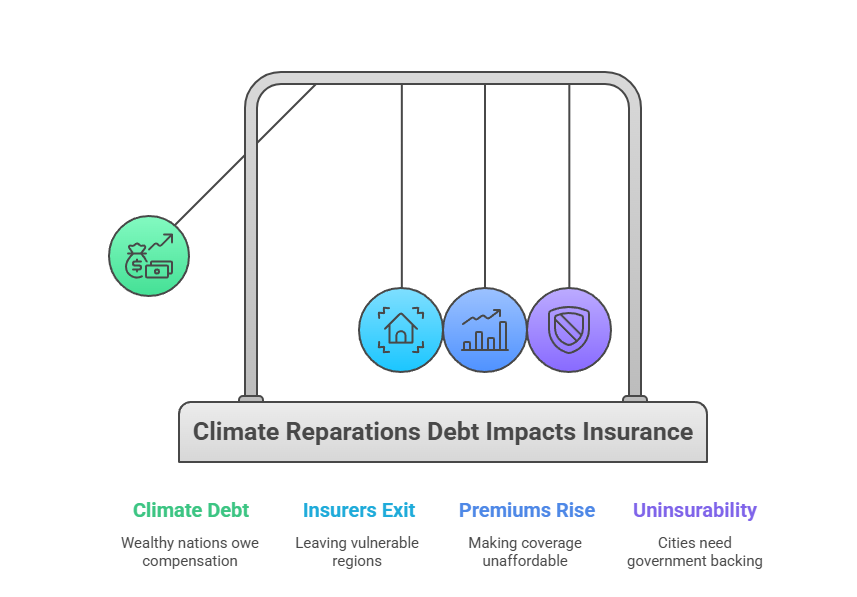

At the heart of this crisis is the concept of climate reparations debt—the idea that wealthy, industrialized nations, which historically emitted the bulk of greenhouse gases, should compensate countries now bearing the brunt of climate disasters.

This was a central theme at COP28 in Dubai, where leaders agreed to launch a Loss and Damage Fund to help vulnerable nations. Yet so far, funding has fallen drastically short:

- Only $700 million was pledged worldwide, compared with the hundreds of billions needed each year.

- The Dubai floods alone could consume nearly the entire fund allocation.

- Countries like Canada, while wealthy, are now also victims of climate change, complicating their eligibility for support.

Critics argue that without a robust financial framework, the concept of reparations remains symbolic, offering little relief to those facing escalating damages.

Insurance Industry on the Brink

For decades, the insurance sector was seen as the safety net for climate-related losses. But today, the industry is under strain like never before.

- In the United States, insurers are exiting hurricane-prone states such as Florida and wildfire-prone regions like California.

- In Europe, premiums for flood coverage are climbing steeply, forcing many households to go without.

- In the Middle East, insurers say mega-cities like Dubai are increasingly “uninsurable” without major government backing.

This is not just an economic problem—it is a social one. Families left without coverage are more vulnerable to displacement, debt, and long-term poverty. For many, a single disaster means starting over with no support.

Who Should Pay? The Global Divide

The debate over who should shoulder climate reparations debt is creating new political divides:

- Developing Nations: Countries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America argue they are least responsible for emissions but most affected by disasters. They demand mandatory payments from wealthy nations.

- Developed Nations: The US, Canada, and European Union states acknowledge responsibility but resist unlimited liability. They prefer voluntary contributions and private-sector involvement.

- Insurance Industry: Insurers are lobbying for government-backed reinsurance schemes, effectively shifting part of the financial burden onto taxpayers.

- Climate Activists: NGOs and advocacy groups argue that oil and gas companies—the world’s largest emitters—should pay directly into global climate funds. Some propose a climate damage tax on fossil fuel profits.

Debt Piled on Debt

For countries already facing fiscal challenges, climate disasters add another layer of strain. Without sufficient external support, the cost of reconstruction becomes sovereign debt.

- Dubai’s post-flood rebuilding is expected to widen the UAE’s budget deficit.

- Canada has already added billions in emergency spending for firefighting, relocation, and rebuilding.

- Developing countries like Pakistan, still recovering from catastrophic floods in 2022, are stuck in cycles of IMF bailouts combined with climate losses, leaving little room for long-term economic growth.

Economists warn that climate reparations debt could trigger a global debt crisis, as vulnerable nations borrow heavily to respond to disasters they did not cause.

Rising Climate Litigation

As governments struggle, courts may become the next battleground. Climate litigation is gaining momentum worldwide:

- In the Philippines, the Commission on Human Rights linked fossil fuel companies to climate-related human rights violations.

- Several US states, including California, have filed lawsuits against oil majors, seeking billions in damages for climate impacts.

- Dubai flood victims are considering legal options to hold corporations accountable for the damages they suffered.

If courts begin awarding financial compensation, it could radically alter the balance of responsibility, forcing polluters to pay billions in reparations.

What Happens Next?

Experts suggest three possible pathways for addressing the growing crisis:

- Expanding the Loss and Damage Fund – Scaling up global climate finance to at least $100 billion per year, funded by carbon taxes on fossil fuel producers.

- Hybrid Insurance Models – Creating public-private partnerships to sustain disaster insurance, where governments absorb catastrophic risk and private insurers handle smaller claims.

- Legal Accountability – Allowing courts to establish binding precedents, compelling fossil fuel companies and wealthy nations to pay reparations directly to victims.

Each approach faces political hurdles, but all recognize one truth: the current system is unsustainable.

A Future Defined by Costs

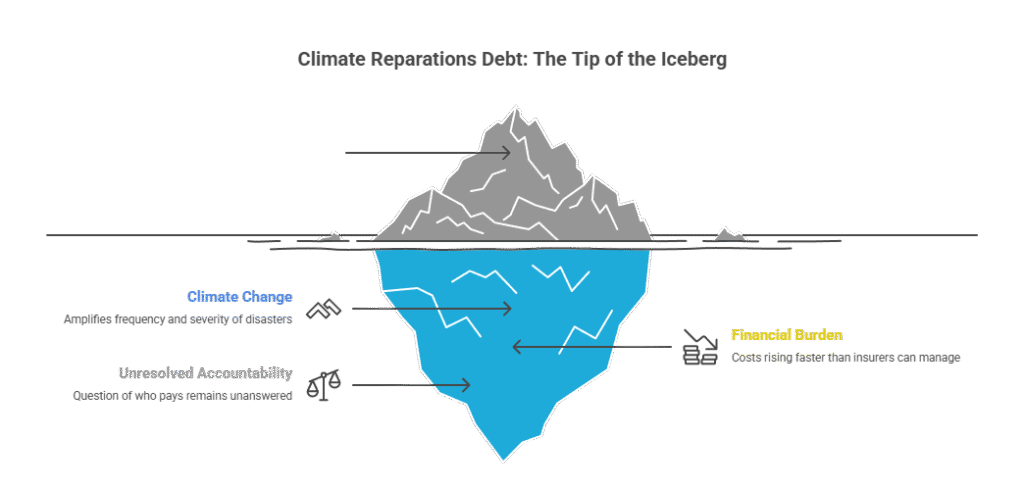

Dubai’s floods and Canada’s wildfires are not isolated catastrophes—they are early warnings of a new global reality. Climate change is amplifying both the frequency and severity of natural disasters, and the financial burden is no longer manageable under existing systems of insurance and debt.

“The costs are rising faster than any country or insurer can keep up,” said Dr. Lina Haddad, a climate policy researcher in London. “Unless the world decides who pays for climate reparations debt, we are heading for a financial crisis on top of a climate crisis.”

As Dubai rebuilds and Canada counts the losses, pressure will mount on world leaders to move beyond pledges and establish binding systems of accountability. With the next round of climate negotiations approaching, the unresolved question of who pays for climate reparations debt is set to dominate global debate in 2025 and beyond.